Welcome to Knotty News #2. This month zipped by.

Here’s the TOC for this issue:

Making The Reddest of the Blacks

Dasha’s Dispatch from Middlebury

Rusana’s Dispatch from Kolyma

Eurasian Knot News

Making The Reddest of the Blacks

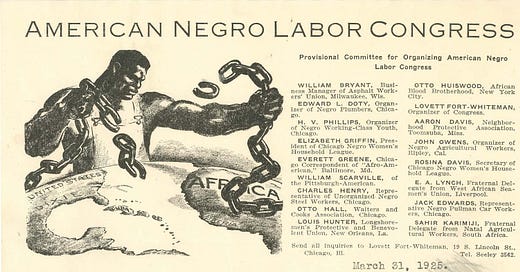

Sean here. Some of you might know that I’m working on a new audio documentary called The Reddest of the Blacks. It’s about Lovett Fort-Whiteman, a Black communist born in Dallas, Texas, and the only known Black American victim of Stalin’s terror. The Reddest of the Blacks will be six episodes covering Lovett’s life and activities in the American Communist Party and in the Soviet Union. It will be released at the beginning of 2024.

I’m not the first to treat his life. Glenda Gilmore wrote the most about Fort-Whiteman in Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights, 1919-1950. Lovett has also popped up in numerous works on Black radicalism. Recent treatments are Joshua Yaffa’s New Yorker article “A Black Communist’s Disappearance in Stalin’s Russia” (Josh and I talked and traded sources for his excellent piece.) and Dick Reavis’ “The Life and Death of Lovett Fort-Whiteman, the Communist Party’s First African American Member” for the Jacobin. Fort-Whiteman has also made appearances in books and articles about Black radicalism in the 1920s and 1930s,

Much of the work on Fort-Whiteman, however, more or less reduces his life to his fate—that is, really, to the last two years of his life. Why was he arrested? Was it political? How does it fit with Stalinism?—drives most treatments. I have my own interpretation for why Fort-Whiteman was arrested in the Spring of 1936. But you’ll have to wait for the documentary to hear it.

The focus on Lovett’s tragic fate isn’t surprising, of course. A Black American victim of Stalin is a novelty. And honestly the only reason why we remember Lovett Fort-Whiteman today is because of his victimhood. An Associated Press journalist, Allan Collison, found his NKVD file in Kazakhstan in the 1990s. Collison wrote a series of articles on American Terror victims. Harvey Klehr and John Hayes published some of the Collison’s Fort-Whiteman NKVD documents in The Soviet World of American Communism. So, Fort-Whiteman’s victimhood has long been front and center to his story.

I wasn’t immune either. I, too, became interested in Lovett Fort-Whiteman because of his fate. I can’t remember the first time I came across his name. But I do remember being drawn to his story and how he ended up in Kolyma in 1939.

But it was only after researching his life did I realize that there’s so much more to his story.

The Reddest of the Blacks will not be a tale of tragedy. It’s a story of struggle. A history of an extraordinary life in extraordinary times. After three years of research from American, Russian, and Kazakh archives and libraries, I now think reducing Lovett’s life to his tragic fate is a disservice. It blankets over how his life, activism, and, yes, his fate, are all part of the struggle to make America fulfill the promise of Emancipation and Reconstruction—for Black people to obtain equality, education, autonomy, self-sufficiency and self-determination. It’s unfulfilled promise that unfortunately still casts a dark shadow over so much of American life today.

Lovett’s story is also about recovery. Like I said, Fort-Whiteman was rediscovered in the 1990s. And everyone who has written about him since has added more pieces to his puzzle. A lot of what I want to say continues this journey of recovery. Of the Whitemans. Of the promise of Emancipation and Reconstruction. Of Black Dallas. Of Black radicalism. Of the antiracist struggle.

For Lovett, this promise began with his father, Moses Whiteman and mother, Lizzie Fort and their life in Dallas, Texas. I’ll write more about them in future newsletters.

I got the opportunity to visit Dallas in October 2022 and go on two Black history tours. Dallas isn’t just the Cowboys and their cheerleaders, J. R. Ewing, oil, and the Kennedy Assassination. The Big D has an extraordinary Black history.

I’ll write more about Dallas in future updates. For now, I just want to share two short audio clip from my visit. Their raw and unedited.

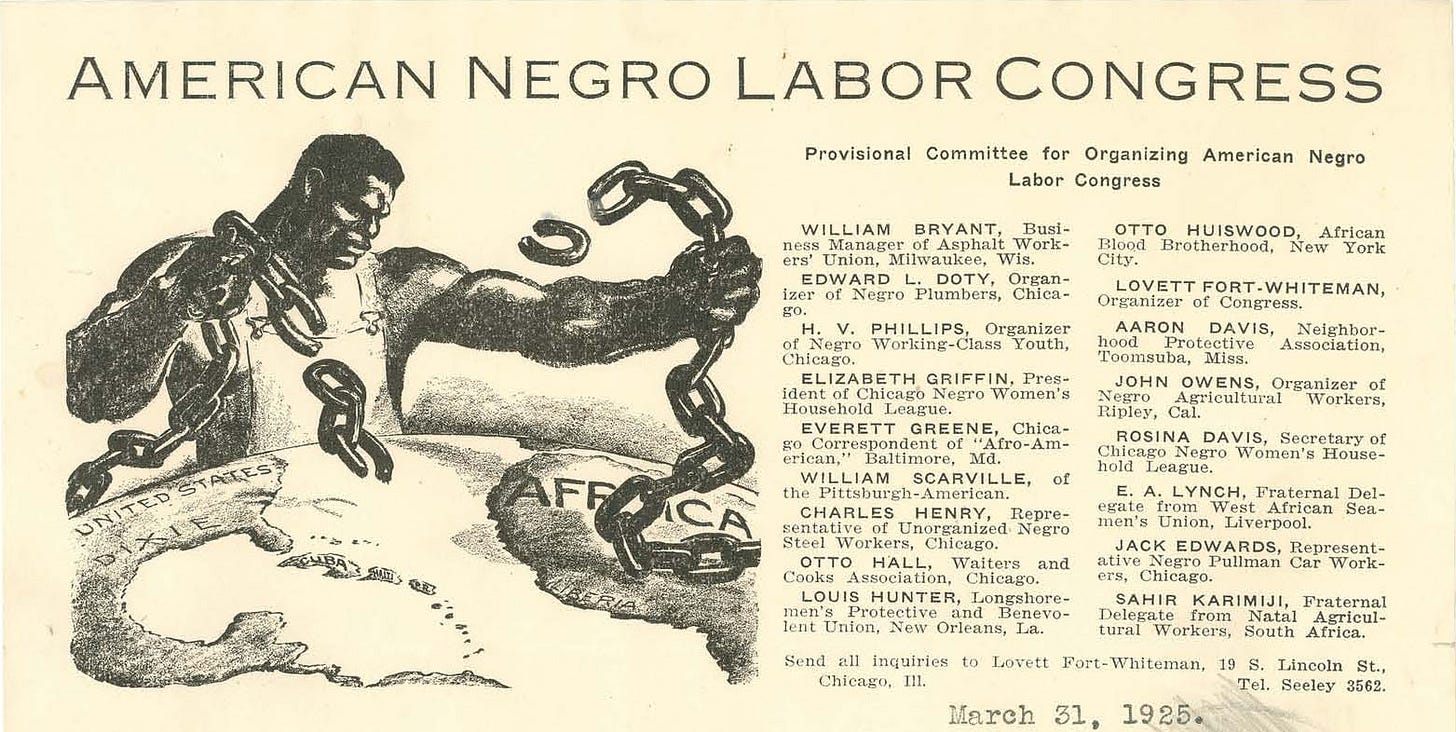

The Freedmen’s Memorial Cemetery is the center of Black Dallasites’ history, memory and identity. A group of Dallas Freedmen bought the land in 1869. It served as the main burial ground for residents of Dallas’ Freedmenstown (later North Dallas and Deep Ellum), one of hundreds of Black communities established in Texas during Reconstruction. The cemetery operated until the city closed it 1906 for overcrowding and disrepair.

Then the Cemetery was mostly forgotten . . . and then the city destroyed it and much of Freedmenstown beginning in the late 1940s to build the Central Expressway. The freeway replaced the old Houston and Texas Pacific Railroad that ran through the heart of the community. Now severed in half, the community known in the 1920s as the “Harlem of the South” began to atrophy.

Here’s what Jim Schutze, journalist and author of The Accommodation, one of the best books on the politics of race in Dallas, wrote about the raising of the Freedmen’s Cemetery in the Dallas Observer in 1999:

Black graves were simply paved over, headstones used as rubble to help fill ditches and low spots.

The existence of the cemetery was never forgotten, but highway engineers, poised in the late 1980s to launch a massive rebuilding of Central Expressway, had hoped there would be as few as a dozen graves that might have to be moved to make room for a new service road.

The more they dug, the more they found. A team of archaeologists working with the Black Dallas Remembered historical society eventually unearthed more than 1,500 bodies that had to be reburied at a cost to the state of between $6 million and $7 million. The archaeologists think as many as 10,000 dead were buried in the original cemetery in a period roughly from slavery to the 1920s.

The memorial being built on the ground of the old cemetery will cost $2 million, only $210,000 of which will come from city funds. The rest is being raised privately. Four of five pieces by Detroit sculptor David Newton, chosen in a national competition, have already been installed.

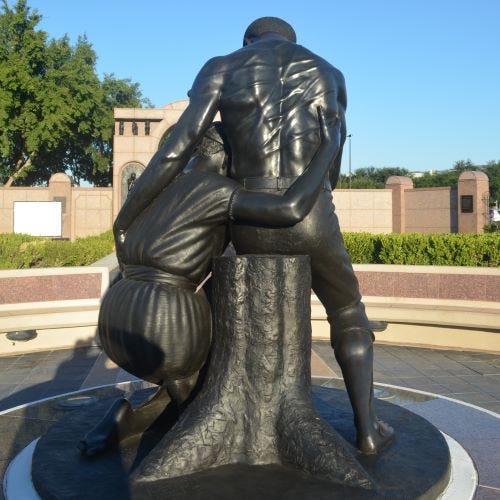

Here’s a clip of my tour guides, Donald and Jocelyn Pinkard, explaining the symbolism of the Freedmen’s Memorial Cemetery’s central sculpture, “The Dream of Freedom.”

Between the 1940s to the 1980s, city officials and real estate developers evicted thousands of residents and leveled about 1,500 structures that made up Lovett Fort-Whiteman’s childhood neighborhood. Homes, churches, businesses, and the Freedmen’s Cemetery were unceremoniously paved over. Black people were displaced to Dallas’ other black communities, particularly to South Dallas. By the 1970s, what was once a vibrant economic and cultural center of Black Dallasite life was gone. What was Freedmenstown is now the State-Thomas Historic District. The past was erased. The present and future totally gentrified.

Here's a clip of Donald Payton, the former City Historical Commissioner and my other Black Dallas history guide as we drove through the State-Thomas Historical District.

That last Black lady Donald mentions is Ruth Mae Sanders. She died at 101 in May 2023. Who knows what will happen to her house. You’ll hear more about Ms. Sanders in Episode two of The Reddest of the Blacks.

I’ll stop here for now. I’ll include updates, sources, and audio clips in upcoming editions of the Knotty News. But they will be short. If you want full access to all my updates on the making of The Reddest of the Blacks, please become a patron of The Eurasian Knot on Patreon.

Dasha’s dispatch from Middlebury

I’m at Middlebury’s Russian language graduate program for a second summer in a row. It’s the program with the famous language pledge ceremony where you vow to speak only Russian for six weeks (“Даю слово!”). It’s a unique time to be immersed in the Russian language, to say the least.

As Russia’s war with Ukraine continues, so does the debate about how to study and contextualize the Russian language. This summer’s graduate curriculum features such courses as “Russia Today: An Inside View,” “Reading Dovlatov in Wartime” and “Decolonization & War in Post-Soviet Space.” For me, the benefit and joy of Middlebury’s graduate program comes not just from the school’s immersion approach to language learning but also the opportunity to study Russian through an interdisciplinary lens. And who doesn’t love adult summer camp?

Rusana’s dispatch from Kolyma

Hello, dear listeners! I wanted to give you a quick update on what I’ve been up to for the past few weeks. I spent most of July doing fieldwork in Seimchan, a small town about 500 km north of Magadan, the regional capital. The town has a fascinating and – like so many settlements along the Kolyma river – gruesome history. Originally a place of Stalin labor camps, it gradually became the agricultural capital of the Magadan region, largely due to its relatively warm climate. It’s hard to imagine how much work was put into making this unforgiving land amenable to agriculture, first by indentured GULAG prisoners and later Komsomol volunteers and workers from all over the country.

Unfortunately, as a consequence of the socio-economic turmoil of the 90s, both local collective farms went bankrupt. The population of Seimchan dwindled to a dismal 1500 people, a sixfold decrease over the last 30 years. Today the town’s landscape is dominated by abandoned and dilapidated buildings, a painful testimony to a failed social experiment.

I came to Seimchan to pick fireweed at a local tea farm organized by a couple from Magadan whose passion for healthy and organic living grew into a business venture. Over the past 10 years – at least—Russia’s been going through some kind of fad for fireweed, or Ivan, tea. Some claim Russians were drinking Ivan tea for hundreds of years before the English took over the market and spread a fashion for black tea from India. Others vouch for numerous health benefits of this plant, ubiquitous in Siberia and the Far East. In any case, my hosts jumped on that train and are now producing several metric tons of tea each summer. Every day, together with a few other farmworkers, I’d travel into former agricultural fields to collect fireweed leaves. There, I was surprised to see dozens of ruinated, rusty greenhouses, some of which, powered by coal, operated year-round. I have to admit there was something eerie about being a wildlife scavenger on the ruins of a former empire.

A local tv station did a news report about the tea farm while I was there. Take a look!

Eurasian Knot News

We have some new announcements as we continue rebranding the podcast. First, we’ve introduced new patreon tiers. It’s kolkhoz themed and it offers new gifts, a discount code for books in Cornell University Press’ Russian and Eurasian catalog, and special updates on the making of the Reddest of the Blacks (which you read about above).

And speaking of merch—we’re opening a Eurasian Knot merch store! We’re not ready to give a link to it yet. But the grand opening will be on August 3. Plan on getting a newsletter with that information next week.

What kind of Eurasian Knot swag would you like? Take the poll:

Keep in mind, the new tiers and merch store are not to make a profit. The money you spend will go back into the podcast to pay Dasha and Rusana a fair wage, pay for equipment and other podcast related expenses, and for the making of the Reddest of the Blacks. Hopefully you’ll find all of these worthy causes to support. So if you’re not a patron, become one today!

Upcoming episodes

Also starting next week, the first of seven interviews on Religion in (Post)Socialist Societies will drop. It’s with Catherine Wanner, an anthropologist from Penn State, on lived religion in the Soviet Union. The interviews were part of REEES’ Spring interview series and treats religion, everyday belief, and practice in Russia, the Republic of Sakha, Romania, Poland, China, and Crimea.

Recent episodes

The Nivkhi of Sakhalin

Almost 30 years ago, Bruce Grant, NYU Anthropology, published In the Soviet House of Culture: A Century of Perestroika, a pioneering study on the Nivkhi of Sakhalin Island. The book touched as several aspects of the indigenous experience under the Russian empire, the Soviet Union, and post-Soviet Russia. The Eurasian Knot decided to revisit In the Soviet House of Culture, and ask Bruce about the work, the history of the Nivkhi, and what his study tells us about indigeneity in Russia today.

Guest:

Bruce Grant is Professor and Chair of Anthropology at New York University. He is author of several books including, In the Soviet House of Culture: A Century of Perestroikas (Princeton 1995) and The Captive and the Gift: Cultural Histories of Sovereignty in Russia and the Caucasus (Cornell 2009). His current research explores the early twentieth-century, pan-Caucasus journal Molla Nasreddin (1905-1931) as an idiom for rethinking contemporary Eurasian space and authoritarian rule within it.

Queer Under Communism

LGBTQ+ history of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union rightly focuses on repression. But queer life cannot and should be reduced to persecution. Thankfully, new scholarship is trying to broaden the historical representation of queer people by listening to queer voices and expression, examining the intersection between medicine, psychiatry, and gay and transgender lives, and the evaluating place of homosexuality in the Cold War contest.

To get a taste of some of these issues, here are three short segments recent research on gender, sexuality and queer under state socialism.

Guests:

Misha Appeltova is starting a new position as Assistant Professor of History at Wake Forest University. Her research focuses on gender, sexuality, and disability in 20th century Central and Eastern Europe. Her manuscript is tentatively titled Embodied Socialism: Gendered Bodies and the Cold War in Czechoslovakia, 1965-1989. She’s also working on a project with her colleague Roy Kimmey that examines the recent rise in anti-gender and anti-LGBTQ mobilization across the globe.

Irina Roldugina is a UCIS Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Pittsburgh. Irina is a historian of early modern and Soviet Russia with a particular interest in social history and history of sexuality. In her book manuscript, Vernacular Queer and Shifting Power in Russia: from the Late Imperial Era up to the 1940s, she explores homosexual emancipation in Russia before and after the Revolution of 1917. Looking at the process from the perspective of non-elite homosexuals, Irina reveals how their same-sex desire was developed, conceptualized, and expressed after the Bolshevik Revolution.

Kate Davison is a Lecturer in the History of Sexuality at the University of Edinburgh in the School of History, Classics and Archaeology. She’s completing a book titled Aversion Therapy: Sex, Psychiatry and the Cold War forthcoming from Cambridge University Press.